Playclothes From Faraway Places

A WARDROBE FOR ALL SEASONS

The legendary fashion house of Haywire is situated at the far-end of Clinkskell’s edgy Cardigan street, opposite the fabled Owd Nina’s restaurant/taxidermy. The shop’s striking exterior is currently a giant mocked-up painting of a ‘Jacobean Whodunit’, complete with ornate picture frame boasting elaborate corners and luxurious wooden panelling. It doesn’t have anything as obvious as a door, but a concealed entrance built into the facade.

The interior is ‘high’ Victorian with large murals of a mountain scene at one end and a faraway fairy-tale castle at the other. Potted palms and over-sized chess pieces are tastefully dotted about to provide interesting focal points. The stock fixtures are rotating wardrobes with clothes neatly piled inside, while free-standing racks display handsome evening gowns and tailored jackets.

Currently the style is all subdued musty tones and second-hand Edwardian Frills, but a month earlier it was brightly coloured velveteen cartoon-suits and beautiful day-frock knitware, popular with the trend-setting likes of Cosmo Strangewood and Sylvia Mogg. Before that, it was decorative summer dresses alongside diplomatic dinner jackets in the heart of winter ~ curiously out of season yet exceptionally desirable.

Haywire was established in 1878 by Thomas Haywire, an inventive tailor and formidable businessman who specialised in elaborate evening wear for high society of the 1890s, 1900s and 1910s. His outfits were often composed of layers of delicate chiffon and an unusual silk that mysteriously corroded if worn more than once ~ a sign of illusive sophistication that greatly appealed to his wealthy, aristocratic clients.

As tastes for disintegrating clothes diminished, Thomas Haywire sold off his remaining stock in the ‘outstanding shopping event of 1919’ and began to style more functional, everyday designs. Often sourcing unusual fabrics from distant places and utilising a unique reprocessing technique, Haywire now catered for the dynamic tastes of the 1920s and 30s. The 1926 Chic Exorcist line was such a favourite with infamous screen-siren Mijanou Reville, that she reportedly would ‘wildly attack with pinking shears’ any garment received that did not have the required Haywire label.

Celebrated couturier Belinda Night begin a career with Haywire in 1942, and her romantic, sensual designs meant that Haywire fashions were continually featured in the most glamorous magazines of the era. However, Thomas Haywire’s refusal to grant interviews caused many writers of the time to speculate that he had in fact drowned some years previously in a floating restaurant disaster. Rumours began to circulate of the ‘unusual practices’ that had allowed the company such esoteric longevity, and his prestigious 1953 Queen’s Service Award to Industry presentation was scandalously disrupted when it became apparent that he had been replaced by a grotesque mechanical mannequin formed out of foul-smelling partially compacted polystyrene.

Very little is known of Haywire for the next decade or so, (a period known by fashion scholars as the ‘Haywire Hushening’) apart from the evidence of a few garments in the collection of noted society hostess Lady ‘Mascot’ Wilkins which includes an unusual purple mourning outfit and a stunning tea gown cut from an unidentifiable cloth.

In 1966 a peculiar article appeared in All Over the Shop magazine by occult novelist Rudolf Rudorff detailing an encounter with Thomas Haywire in a private auction room. Although displaying more than a whiff of the florid fiction Rudorff was known for, one paragraph in particular does provide potentially revealing insights ~

‘He was pale, probably because he spent most of his life sitting in the dark. His lips were always black, possibly because of a rumoured addiction to liquorice. He wore dark Edwardian velvets with shirts of embroidered white muslin: his vampire and dying-swan looks. He constantly posed crossed-legged against facsimile pillars salvaged from an abandoned Victorian photography studio. He wore over-sized silver rings and a black flower in his lapel. His hair was a well-coiffed mass of dark bronze, his demeanour genial yet imposing.’

It was shortly after the publication of this feature that a remodelled Haywire shop managed by Belinda Night reopened for business ~ delving back into the past with antique clothing reworked for modern youth. Once the word got around, second-hand outfits for men and women flew off the shelves. Rampant revivalism was the order of the day and Haywire had a seemingly endless supply of vintage clothes, all unerringly on-trend. It was as if they could simply go back in time and select what was needed.

Perhaps such undemanding commerce was deemed a little tasteless. In 1968 the store had a complete redesign to introduce their extremely successful Country Moments range: elaborately tailored out-of-doors tweed and crushed-velvet rambling ensembles, complete with the deftly ludicrous oversize tam-o’-shanter style cap that came to be consistently devoured by the 1970s fashion-hungry.

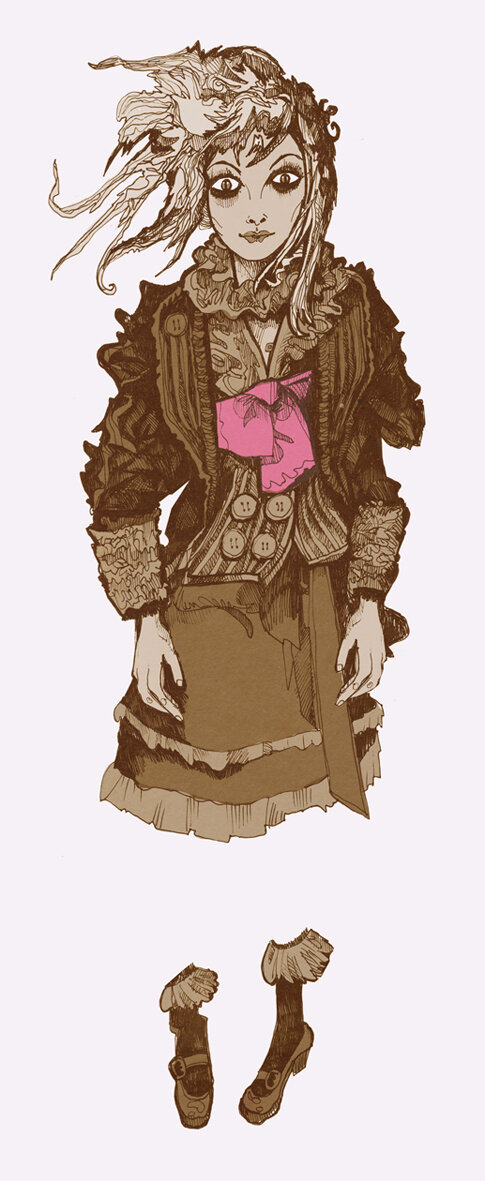

Haywire have maintained their relevance through an uncanny ability to predict and react to fashionable trends. Very few British towns or cities are currently without pervasive youth-cult MASS (Mostly Almost Sepia Society) huddling in doorways and underground markets, unsettling passers-by with their constant group humming, out-of-joint garb and static poses snipped from a Victorian scrapbook. Their sepia-toned outfits matched with a single luminously bright accessory ~ all exclusively supplied by Haywire.

Did Haywire foresee that their audacious ‘Scrunched Edwardian’ aesthetic would resonate with such a large minority of today’s young people? An unnaturally youthful Belinda Night languidly explains with a mischievous smile that certain Haywire styles are permanently du jour, and it’s often an wearisome process as the rest of the country slowly catches on.

Anyone who enters the fashion house of Haywire has their own reasons for doing so. For some it is a natural act of devotion, to effectively costume an illusive identity. For others the predetermined result of a chance encounter, or a peculiarly convoluted clause in an antiquated marriage contract. But once through the concealed doorway and entwined within the fabric of this world, they will happily find, it is completely impossible to escape.

Amelia Fulford,

Society Illustrated, 1984