A Spare Tabby at the Cat’s Wedding (LP Edition)

A Spare Tabby at the Cat’s Wedding (LP Edition) (GEpH004LP) 2010

Arrived from the Elsewhere

In the early part of the Twentieth century, clubs and country houses of England resounded with the cries of merrymakers playing card games as diverse as Oh! Butterwick and Cakeshop Thief. Many a wet afternoon or autumnal evening was pleasantly whiled away in this manner, as specialist cards have long found favour amongst the idle rich, and are numerous in their scope and popularity.

During this period new games were devised and manufactured to meet an insatiable interest, wand while many of us today still entertain our dinner guests with a round or two of Misty Allotments, some once-popular games are now only played by the enthusiast, and many are now sadly long-forgotten.

However, for the scholar who researches into this area, the name of one ‘lost’ game does tend to crop up with uncanny irregularity, that of A Spare Tabby at the Cat’s Wedding.

Its first recorded occurs within the autobiography of Lord Burlington-Mumford (1922) as

’that devilishly addictive card-game, the current obsession of my daffy niece and her lacklustre cohorts that sabotaged enjoyment of Evensong for all eternity’.

It is also believed to be the original ‘questionable entertainment that wouldn’t burn’ Myrtle Devenish based her 1926 novel Gawd, What a Mistake upon, and fictional theorist Sukie Partington claims it to be the reason why the entire South-Western railway network ground to a halt and disappeared during the summer months of 1929.

The most complete account of ASTATCW can be found within the exceedingly rare Memoirs of Ruined Ambition by Admiral ’Tuffy’ Piper. Published privately in 1935 by an unstable relative, this unwieldy tome is ostensibly a tedious catalogue of one man’s, grievances against humanity and ruthless enterprise. However, within the final chapters the tone changes considerably, and details emerge of how an unusual pack of playing cards left behind by a ‘mysterious visitor from the North’ became the obsessional lament of the ages aristocrat. On the whole the style is florid and nonsensical, clearly a result of the author’s confused state of mind, but one passage in particular provides interesting reading:

‘I played the infernal game for 32 hours straight, and at the end I was no nearer being able to leave. The sequence was wrong and I could no longer be kept awake. Whilst asleep I found myself once again in that terrible, terrible village. This time it was a baking hot day, and all around the streets, shops and houses were festooned with elaborate decorations, as if it were the celebration of another kind of Mayday. I felt more uneasy than I had when taken there during the night-time.

I asked a curious passer-by, dressed in the manner of a Vaudevillian magician, what was about to take place, but she just tapped her nose twice and smiled. As I sat down in the market place and cried, the sun beat down upon me and a familiar noise began to swirl around like like fog. It was the horrible sound of cats laughing.

I awoke to find a wedding ring on a handkerchief beside me, and behind my four-poster bed an ancient monarch and her ghastly entourage were slowly fading away.’

While this excerpt is perhaps a sad example of delirium, it does provide some interesting clues as to the nature of ASTATCW.

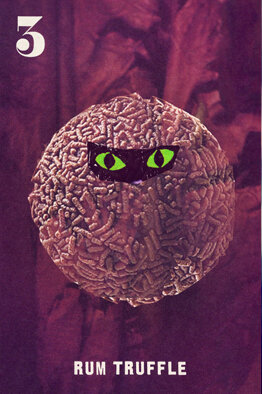

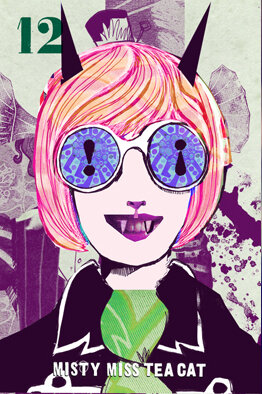

Today, the game seems quite unplayable. Not only are there no complete sets currently in existence, but no copies of the rather vital ‘rules of the game’ card have ever been found. At the time of writing, the Society of Unusual Pastimes (SOUP) has sixteen cards within its archive, while a private collector, known only as Mr.B and infamous for his wry and deceitful telegrams, claims to have 'almost a complete set’ which also includes an additional card, advertising an ‘alternative version for you, your friends and family to play’. A possibility that provides more questions than answers.

The object and purpose of ASTATCW has itself left scholars of English pastimes and entertainments an intriguing puzzle. The extreme scarcity and incomplete nature of what was once a reasonably popular card game is perplexing, and has predictably led to some outlandish theories, the gist of these being that this is a game not to be played, and that these cards are an example of objects that have ‘arrived from the elsewhere.’ None of the usual manufactures of the era have a record of production, causing speculation that it was a ‘collectors game’ where each card was issued separately by a specific company, such as a children’s confectioners.

The most inventive, not to say unsettling interpretation of ASTATCW has been devised by the noted ‘thrift-store Historian’ Sir Douglas Frisbee-Milverton. He holds the view that ASTATCW was an early example of an ‘interactive game, that used music to propel the player’s imagination along a specific path, towards a specific goal.

The missing instructions apparently contain details of the actual compositions that were intended to be played as musical accompaniment. He also ventures the disquieting opinion that the very act of playing ASTATCW operates as a form of ‘arcane key’ and has published a series of increasingly bizarre articles within specialist periodicals upon the subject. The latest of these claims that as a direct result of his own research:

‘Somewhere in the capital, made more horrible by thin disguise of bowler hat and fancy suit, they are at large, mixing with the crowds, perhaps sitting on the top deck of an omnibus; perhaps even calling at a shop to buy their foul tobacco. The game is not to be played, the music is not to be played until all those who gain from its significance have had their lights quenched.’

Although the disturbing claims of Frisbee-Milverton carry an uncanny weight, we can all rest easy as the music he describes has no basis in reality whatsoever.

Perkin Undercroft,

Mystery Collector Magazine, 1972